Every hour of every day, many thousands of airline pilots do something that, on the face of it, seems silly. Just before landing, the flying pilot lowers the landing gear, and three bright green lights illuminate. They both see the lights, and then the non-flying pilot asks: “Landing gear down?” The flying pilot must, by law, respond: “Check - three down and green.”

Every hour of every day, many thousands of airline pilots do something that, on the face of it, seems silly. Just before landing, the flying pilot lowers the landing gear, and three bright green lights illuminate. They both see the lights, and then the non-flying pilot asks: “Landing gear down?” The flying pilot must, by law, respond: “Check - three down and green.”

They both know the landing gear is down the second the lights go on, but they still have to ask the question, and they have to hear an answer.

This is not done just for just the landing gear. There is rarely a move a pilot makes that isn’t confirmed by the pilot sitting next to him. Regardless of how many years of experience they have, commercial pilots can hardly flip a switch without confirming it with their (often much junior) partners.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules that make it a crime not to do so are not excessive government oversight. It’s that the pilots and the FAA know something most of us find very hard to admit: everyone - even those with long experience doing something - are capable of making mistakes. Everyone is capable of forgetting something. And when forgetting can get people killed, you make a list and check it every time.

Human Error Is A Myth

To my way of thinking, there is no more dangerous concept than the idea that human error has caused an accident. It’s dismissive. When we attribute a mishap to human error, we think “they made a mistake” and in some small part of our brains believe “I wouldn’t have done that.”

It’s not an error in your humanity that you forget things or miss clues or make mistakes; that is human nature. It is what we all definitely do all the time. It’s only when we do these things during high-risk activities that they are mislabeled “human error.”

In any system, boating included, we know going into it that the human involved will make mistakes. This might be the most important thing to understand in managing your own safety while boating:

- You are going to screw up. You are definitely going to make mistakes. You are definitely going to forget something important.

- Checklists are the things that take the load off your humanity and help you prevent errors you might make in an emergency.

Three Types of Lists

In commercial aviation, they break checklists down into normal and non-normal operations. (Non-normal is just a strange word for “emergency”), but in boating I like to make three types of lists: condition and preparedness, emergency, and post-docking/anchoring.

Put another way, they are before you leave, when things go sideways and when you get back lists.

Before You Leave Lists

Obviously, there are things you should check that are specific to your vessel; these are manufacturer’s suggested maintenance and vessel checklists, often provided in the owner’s manual. They are what I call “gas and oil” checklists, and they should not be ignored. If you haven’t read that manual from cover to cover, you are making your first mistake.

You’ll also likely have your own checklists for your boat and those specific to the trip you are going on. (These are your trip checklists: sunscreen, food, clothing, etc).

However, it’s the final pre-sail safety check that most boaters miss. This is the preparedness checklist that stops emergencies before they happen and ensures you are prepared if they do. While you don’t need to perform this like airline pilots with their “challenge” and “response” format, you should go through each item on the list every time before heading out.

If you already have a presail safety checklist, congratulations. If it is tougher than mine, I’d love to see a copy.

This checklist should feel at least a little burdensome. Take mine and modify it for your vessel. If you think I went too far, remember my last job and reconsider.

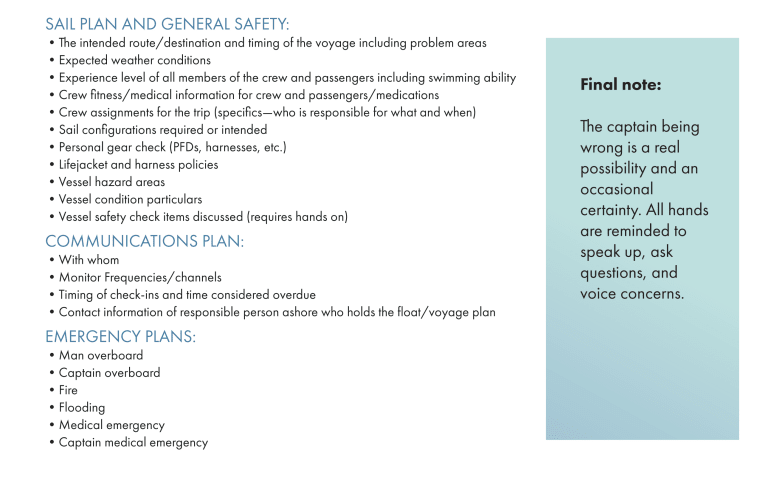

Also vital is the pre-sail safety brief. This is a list of things to discuss with everyone on board before leaving the dock. This checklist will ensure you don’t forget to talk about or consider anything important prior to throwing off the lines. Again, use mine if you like.

When Things Go Sideways

Pilots have a QRH, the Quick Reference Handbook. Smoke in the cabin? They break out the QRH. Engine stall? The QRH has a procedure for that. They will then go through each item on the list, line by line, until the problem is (hopefully) solved.

I know what you are thinking: I can make a QRH for my boat. Yes, you can. Now get on it. Because if forgetting under normal conditions falls somewhere between possible and easy, forgetting during an emergency is somewhere between likely and you are definitely going to.

As a reality check here, consider that I’ve never investigated a man-overboard incident where the captain of a vessel did not forget to do something from his own MOB procedures. Never. Not once. While this is usually about inadequate practice with emergencies (a blog post for another time), you should definitely make a QRH for yourself and pull it out every time there is an emergency. What is an emergency? If it’s something you would call pan pan for, a procedure for it should be in your QRH.

After-Docking Lists

I’ve seen a lot of boaters who have these kinds of lists. You love your boat, and you want it to be left in good condition, of course. But this is also a good time to make sure all of your emergency gear is where you think it is and in the condition you want it to be in.

The reason you want to check your safety gear now, when you won’t need it, is because you are human. If something went missing during your trip and you don’t find out until just before throwing off the lines next time, you are less likely to handle that issue before heading to sea again.

If you find out the PLB in your life jacket is damaged during your after-sail check, you’ll buy a new one before your next trip. Find out your PLB is broken 10 minutes before you start the engines, and you’ll make an excuse and promise yourself to pick one up next week.

Get to Work

If it feels like I just assigned you a lot of homework, I’m sorry. But not really. This kind of work is what made commercial airlines as safe as they are. What checklists do, for free, is take the burden off human nature and help stop our mistakes before they can have an impact. One pilot will ask another if he sees the green lights because he knows he is capable of not noticing that one is red.

If a 20-year professional airline pilot has no problem asking for someone else to agree that he sees three green lights, who are we to think, "I know what I am doing matters"? Because it doesn’t. Before you leave the dock, sit down and make a list of all the things you don’t want to forget. Make lists of all the things (when you are calm) you should do in an emergency. Boat like a pilot and acknowledge you are human and fallible. Doing so will make sure you and your passengers 'land' safely at your next destination.